A Captive In Africa

This is part of an illustration by Frank Hoban of Tarzan And The Leopard Men, a story by Edgar Rice Burroughs in the September 1932 issue of Blue Book magazine:

Elsewhere on Bondage Blog:

This is part of an illustration by Frank Hoban of Tarzan And The Leopard Men, a story by Edgar Rice Burroughs in the September 1932 issue of Blue Book magazine:

Elsewhere on Bondage Blog:

This photograph of half-clenched fists from the 2015 ErosBlog archives is barely suggestive, the way it’s been framed and cropped. But to someone with even a little bit of erotic imagination, it might as well be explicit:

Photo is originally from Kink.com’s Hogtied.

Elsewhere on Bondage Blog:

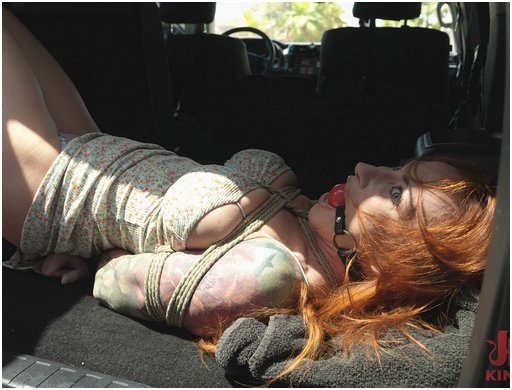

It used to be that no self-respecting BDSM kidnap scene was complete without a shot of Our Heroine tied up in the trunk of a big sedan. But this world is no longer as it was, and big sedans are getting mighty scarce. “Throw her in the back of the SUV” doesn’t work quite so well as fetish fuel; the psychodynamics just aren’t the same. But every now and then, we find a kidnap-pornographer who makes it work:

This is the lovely Sophia Locke in a Kink.com shoot called Mr. Sicko and the Little Lady.

Elsewhere on Bondage Blog:

His wife bought him a pair of handcuffs for his birthday. She was hoping to spice things up in the bedroom, and my friends, her plan is fuckin’ working:

From Kinky Delight.

Elsewhere on Bondage Blog:

Well, this is embarrassing. I have a folder of links to make blog posts from, but I did not realize a certain vulnerability. I rely heavily on Archive.org when saving links, and it (the Internet Archive) has been offline for a week due to denial of service attacks. There are 72 items currently in my “stuff to blog” bookmark folder, and all but seven of them are inaccessible today because of the outage. Whoopsie!

This submissive bondage blonde is from a Margaret Brundage cover on the January 1934 issue of Weird Tales magazine:

Elsewhere on Bondage Blog: